Raw notes – to be formatted

Review

Marty Cagan acknowledges in “Inspired” that most of our products and features won’t meet expectations, and the ones that do require a lot of iteration to reach that point. I believe this is THE most important observation about product development. This book does a great job of articulating that phenomenon and proposes a robust way to navigate it. This is the best book on validating product ideas that I’ve read. I will forever be sharing this book.

Product management theory is cleaner when you assume you’re pre-product (e.g. going from zero to one). I’d love to see another book from the author about product validation in more established companies for more incremental work.

I found the authors obsession to ‘coin a phrase’ a little frustrating, its an emerging trend in Product Management writing.

Key Takeaways

The 20% that gave me 80% of the value.

- Make sure you’re building The Right It before you build it right

- Most new products will fail in the market even if competently executed

- Great execution can’t save you if you’re building The Wrong It

- You need to combine great execution with a product that’s The Right It

- The Right It: an idea for a new product, if competently executed, will succeed in the market

- You can’t tell if something is The Right It in ThoughtLand. You have to take it to the market

- Other peoples data and opinions are not valuable, you need to collect your own data (YODA)

- Your market data must come with skin in the game. Time, money or reputation

- Thinking tools can help you articulate your idea as a testable hypothesis

- Frame your idea as a Market Engagement Hypothesis in the XYZ format:

- At least X% of Y will Z

- Then find a smaller more accessible market where you can test that same hypothesis (xyz)

- Frame your idea as a Market Engagement Hypothesis in the XYZ format:

- Pretotyping tools can quickly validate your market engagement hypothesis → they answer should we build it?

- Mechanical Turk, the Pinocchio, the Fake Door, the Facade, the YouTube, the One-Night Stand, the Infiltrator, the Relabel

- Weigh evidence based on how much skin-in-the-game people provide

- E.g. ignore opinion but value pre-orders

- There’s a hierarchy: Money > reputation > time > everything else

- Tactics and mindset:

- Think globally, test locally

- Think cheap, cheaper, cheapest

- Testing now beats testing later

- Tweak it and flip it before you quit it

- The end to end process:

- Start with an idea

- Identify the Market Engagement Hypothesis

- Turn the MEH into a say-it-with-numbers XYZ Hypothesis

- Hypozoom into a set of smaller, easier to test xyz hypotheses

- Use pretotyping techniques to run experiments and collect YODA

- Use Skin-in-the-Game to weigh YODA.

- Decide on the next step (go for it, drop it or tweak it)

- Follow these steps reduces your probability of failure. If you fail you’ll fail well. If you stick with it, you’ll find an idea that works in the end.

- Make sure you are building The Right It, and make sure that you really care about it before you build it right

In-depth Summary

Part 1: Hard Facts

The Law of Market Failure

Failure is not an option- Failure is the most likely outcome. Most new products fail.

- Treating failure as the most likely outcome is an effective mindset → it aligns you to reality

- Failure is a beast.

- When new products are brought to market, failure is the rule not the exception.

- The law of market failure: Most new products will fail in the market, even if competently executed

- Market failure: any result from an investment in a new product that is less than or the opposite of the expected result

- Market Success: any result from an investment in a new product that matches or surpasses the expected result

- It’s important to be explicit about your success criteria before you get started

- Approximately 80% of new products fall short of their original expectations and are categorized as failed, disappointing or cancelled. (Nielsen Research)

- The statistics on new-product failure are clear, consistent and convincing

The Success Equation

- Success often depends on a number of key factors. So you end up with something like this…

- Right A x Right B x Right C x Wrong D x Right E = Failure

- Right A x Right B x Right C x Right D x Right E = Success

- The successful outcome depends on n key factors being right, there are 2n−12n−1 ways to fail and only one way to succeed

- It only takes a single key factor to go wrong and you won’t succeed

Too Smart to Fail?

- Google and Microsoft although incredibly successful have had a string of product failures too

- Even the most competent and innovative of companies will have 5 failed products for each successful one (but they still do better than conservative companies)

- The law of market failure is blind. It doesn’t care who you are or what you know

- Experience and competence are powerless when applied to a product that the market is not interested in. They tend to make failures bigger and more public as we make bigger investments and set unrealistically high expectations.

Failophobia

- Most new products will fail. Failure will happen in many ways. Competent execution is not enough to defeat the Law of Market Failure.

- Google the company understands and accepts failure is an inevitable by-product of innovation BUT each employee wants their thing to succeed and doesn’t want it to fail.

Flop

- The author interviewed many people at Google about project failures, most projects failed for three reasons:

- Failure due to Launch, Operations, or Premise (FLOP)

- Launch failure is when sales, marketing or distribution efforts fail to reach the intended market with necessary visibility or availability. Your target audience don’t know it exists, don’t know enough about it or can’t get it

- Operations failure is when your products design, functionality or reliability fails to meet a minimum threshold of user expectations.

- Premise failure is when people just aren’t interested in your idea. They know about it, understand it and believe that it does what it promises reliably and efficiently. They can find it. They just don’t care.

- Ultimately most products fail because not enough people want or need them.

- People point fingers and assign blame to others when products fail. BUT push them to think again and often they’ll concede the team did a good job.

- A small % of products fail because they were poorly launched or built → the majority fail because they are the wrong product idea to start with

- Most new products fail not because of incompetence in design, build, or marketing but because they are not what the market wants.

- We build it right BUT we don’t build The RIGHT IT

- You’ve got the right it only when enough people want or need your product to justify developing it.

- Make sure you are building The Right It before you build it right.

The Right it

- The Right It: an idea for a new product, if competently executed, will succeed in the market

- Even if you have the right it, and competently execute, you can’t guarantee success, somebody could beat you to it, or do it better afterwards.

- Defining the right it is necessary but not sufficient. BUT it will dramatically increase your chances.

- The Wrong It: an idea for a new product that, even if competently executed, will fail in the market.

- The more time and effort invested into the wrong it, the bigger the failure

- The definitions pose two questions….

- Why do so many waste their experience and competence executing the wrong it?

- How can you know if it’s the Right It before we invest too much?

Thought-land:

- Why do so many waste their experience and competence executing the wrong it?

- Companies with bad track records of product success don’t change their research approach

- Most market research isn’t done in the actual market, but in magical Thought-land

- People are guessing, assuming, sharing opinions and biased judgements, disagreeing even before the market has been tested

- You can’t determine if an idea is The Right It through thinking (yours, others or expert opinions won’t help you)

- At best our predictions are right some of the time

- You can’t deduce or induce The Right It in Thought-land → it has to be discovered through experimentation

- Hocus-Pocus Focus Groups

- The author doesn’t value focus groups or surveys

- He recommends doing the technique he’s about to share in additional

- If the two types of research disagree, then one of them is lying

- The four trolls of Thought-land

- Lost-in-translation: If your product doesn’t exit, when you speak to others about it they’ll imagine something different. They will judge the idea based on their interpretation of it

- Prediction problems: People are bad at predicting of they will want like or use something they haven’t experienced.

- Skin-in-the game: People love to give opinions and advice, but it’s done without much thought if they don’t have skin in the game (a vested interested n an outcome / something to lose or gain)

- Confirmation bias: humans seek evidence to confirm existing beliefs and dismiss things that run counter to them

- Thought-land produces subjective, biased, misguided and misleading opinions

- Though-land produces a lot of false positives and false negatives

- Given 80% of products don’t meet expectations, we can presume this is a powerful force

- There at too many ways to misjudge an idea’s likelihood for success

Data Beats Opinions

- At Google the author quickly found that he needed data or nobody would support his opinions

- But data wasn’t good enough, for people to listen to it, it would have to be…

- Fresh: what’s true a few years ago might not be true now

- Relevant: data must be directly applicable to the product or decision being evaluated

- Trustworthy: Provenance should be known. You need to know where the data came from and how it was collected.

- Statistically significant: it must be based on large sample and not attributable to chance

- Be cautious when using other peoples data. Other peoples data is collected and compiled by other people, for other projects, in other places with other methods and for other purposes.

- Only use it to supplement and inform your actions

- When you think of a new business idea, there are 5 scenarios. None of which are powerful enough to make a decision on about your idea. Their experience, results and data are not necessarily applicable to your ideal

- You are the first person to come with the ideas. There’s nothing in the world like it (unlikely)

- Other people have the same idea and.. .

- they chose not to pursue it (we can’t learn anything)

- they are actively pursuing it, but have not launched yet (can’t learn anything)

- they pursued it, launched it and it failed (some data, but it could be to many factors)

- they pursued it, launched it and succeeded (doesn’t mean we’ll succeed)

- Get your own data to validate ideas. It must be fresh, relevant, trustworthy, and significant

IDEA RECAP:

- The Law of Market Failure: Most new ideas will fail in the market—even if competently executed.

- Most new ideas fail in the market because they are The Wrong It—ideas that the market is not interested in regardless of how well they are executed.

- Your best chance for succeeding in the market is to combine an idea that is The Right It with competent execution.

- You cannot depend on your intuition, other people’s opinions, or other people’s data to determine if a new idea is The Right It.

- The most reliable way to determine if a new idea is likely to be The Right It is to collect Your Own Data (YODA).

Part 2: Sharp Tools

Thinking Tools

- Clarity of thought is paramount. If your new product idea is vague, imprecise, ambiguous or open to interpretation, you don’t have a solid foundation

- You need to articulate your idea clearly before you can design tests

Market Engagement Hypothesis

- For an idea to succeed in the market, a number of key factors have to line up

- Right A x Right B x Right C x Right D x Right E, etc = Success

- If the market doesn’t want to engage with your idea you’re done.

- If there’s no market there’s no way

- The Market Engagement Hypothesis: identifies your key belief or assumption about how the market will engage with your idea.

- Will they want to learn more about it, explore it, try it, adopt it, buy it?

- Will they buy it again or recommend it to friends?

- MEH is a short sentence that encapsulates the basic premise of your idea along with how you expect the market to engage with it / respond to it

- Your MEH should be clear, testable and expressed using numbers

- Example:

- Idea: Webvan, online ordering and home delivery of groceries

- MED: Given the option, lots of households will regularly choose to buy groceries online instead of going to the super market

Say it with numbers

- Avoid vague terms and use numbers whenever possible. Numbers turn fuzzy opinions into testable hypothesis

- Fuzzy opinion: if we make our subscribe button wider, we’ll get a few more clicks on them

- Testable hypothesis: if we make our subscribe button 20% wider, we’ll get at least 10% more subscribers

- Fuzzy thinking is an invitation for trouble

XYZ Hypothesis

- Turn your Market Engagement Hypothesis into an XYZ Hypothesis

- E.g. At least X% of Y will Z

- E.g. At least 10% of people who live in cities with an Air Quality Index level greater than 100 will buy a $120 portable pollution sensor

- X= a % of your target market

- Y = a clear description of your target market

- Z = how and to what extent the market will engage with your idea.

- The XYZ Hypothesis helps make implicit assumptions explicit. It’s a de-fuzzer.

- Its the first step in tracking your position and measuring progress too.

Hypozooming

- Hypozooming takes the XYZ hypothesis, and makes it testable. Smaller, simpler and more verifiable version of your hypothesis.

- Y = your ultimate target market, everyone in the world who’ll buy your product when available

- y = a manageable, easy-to-reach initial test market

- Make it small, but larger enough to be statistically significant

- Example XYZ =At least 10% of people who live in cities with an Air Quality Index level greater than 100 will buy a $120 portable pollution sensor

- xyz = At least 10% of Beijing Tot Academy parents will. buy an 800-yuan portable pollution sensor

Pretotyping Tools

- Author shares the story of IBM doing a Wizard of Oz style experiment with speech-to-text ‘technology’ using a fast typist hidden from view. They learnt a lot.

- This was more pretending that prototyping. Hence the word: Pretotyping.

- The author says the word prototype has been used too broadly.

- Prototype is normally used to describe testing how something can be built

- Pretotype is about validating quickly and cheaply if an idea is worth using.

- Pretotype implies schedules are measured in hours, and days and budgets that rarely exceed a few hundred dollars.

In Search of Pretotypes

- In most cases a pretotype can save you from wasting time on a well executed market failure

| Mechanical Turk | Replace a costly, compete or yet-to-be-developed technology with a concealed human being performing the functions instead. |

| Pinocchio | Creating a mock-up or nonfunctional prototype and using it as if it’s were functional |

| Fake Door | Get data on how many people are interested in your idea by putting up a ‘front door’ to pretend that the service exists – E.g. create an online advert for a product that doesn’t exist yet Super efficient and effective BUT contains an element of deception (so be generous with the people who knock on the door if you can) |

| Facade (fake door variant) | When a potential customer knocks on the door, someone answers and something happens. They may even get precisely what they’re looking for. ◦ E.g. launch a car selling website and actually sell a few cars |

| Youtube | Make a youtube video demonstration video that makes it look like your software product is real (using prototyping tools). Create a website around it and allow people to register interest. |

| The One-Night Stand | Spin up a product or service for just as long as you need to get the data you need. Commit just long enough to get the data you need. E.g. Virgin Airlines started by chartering a single plane for a single trip E.g. Tesla used portable car showrooms to gauge demand in new areas Test a little before you invest a lot (try it for a few hours, weeks or days before making a commitment). Validate a longterm XYZ hypothesis, with a short-term xyz experiment. |

| The Infiltrator | Creating or manufacturing a product on a small scale (with minimal investment) and sneaking it into an existing sales environment. |

| The Relabel | Make a minor change to an existing product (e.g putting a different label on) and pretend it’s something different to gauge interest in it |

- Be mindful that some products depend on repeated use and engagement to be successful

- Can you convert the initial buzz into ongoing interest

- Think about the return on your Pretotyping Investment

| Pretotypes answer… | Prototypes answer… |

| Would I use it? How, how often, and when would I use it? Would other people buy it? How much would they be willing to pay for it? How, how often, and when would they use it? ….. Should we use it? | Can we build it? Will it work as intended? How small/big/cheap/energy-efficient can we make it? |

- Pretotypes have three key attributes:

- produce YODA your own data with skin in the game

- can be implemented quickly

- can be implemented cheaply

- Analysis tools can help you decide…

- How many different experiments do you need to run

- How much data do you need to collect

- When can you stop testing?

Analysis Tools

- Skin in the game: having something at risk. Reputation, time or money

- The game is bringing a product to market.

- As an entrepreneur, inventor or investor in a new idea you have no choice but to have some and often a lot of skin in the game.

- Skin in the game indicates commitment, seriousness and thoughtfulness

- Don’t put too much of your own skin in the game into an idea unless you can demonstrate the market is interested enough to put their skin in the game too.

- Different types of evidence should be given different weights

| Type of Evidence | Examples | Skin in the game points |

| Opinion | Great idea. | 0 |

| Encouragement, discouragement | Go for it. | 0 |

| Fake email address or phone number | 121312@fakeemail.com | 0 |

| Comments or likes on social media | This is ideas sucks. Thumbs up. | 0 |

| Surveys, polls, interviews | How likely are you to buy? | 0 |

| A validated email address with permission to email product updates | Submit your email to subscribe to product updates | 1 |

| A validated phone number with understanding that you’ll call with updates | Give us your phone number so we can call you about product x | 10 |

| Time commitment | Come to a 30min product demo | 30 (1pt./min) |

| Cash deposit | Pay $50 to be on the waiting list | 50 (1pt./$) |

| Placing an order | Pay $250 to buy one of the first 10 units when available | 250 (1pt./$) |

- A validated email is the smallest piece of evidence that’s considered skin in the game

- Clearly a $50 deposit is so much more valuable than an email address

- To be convinced in an idea, you should need to see real data (YODA) with skin-in-the-game

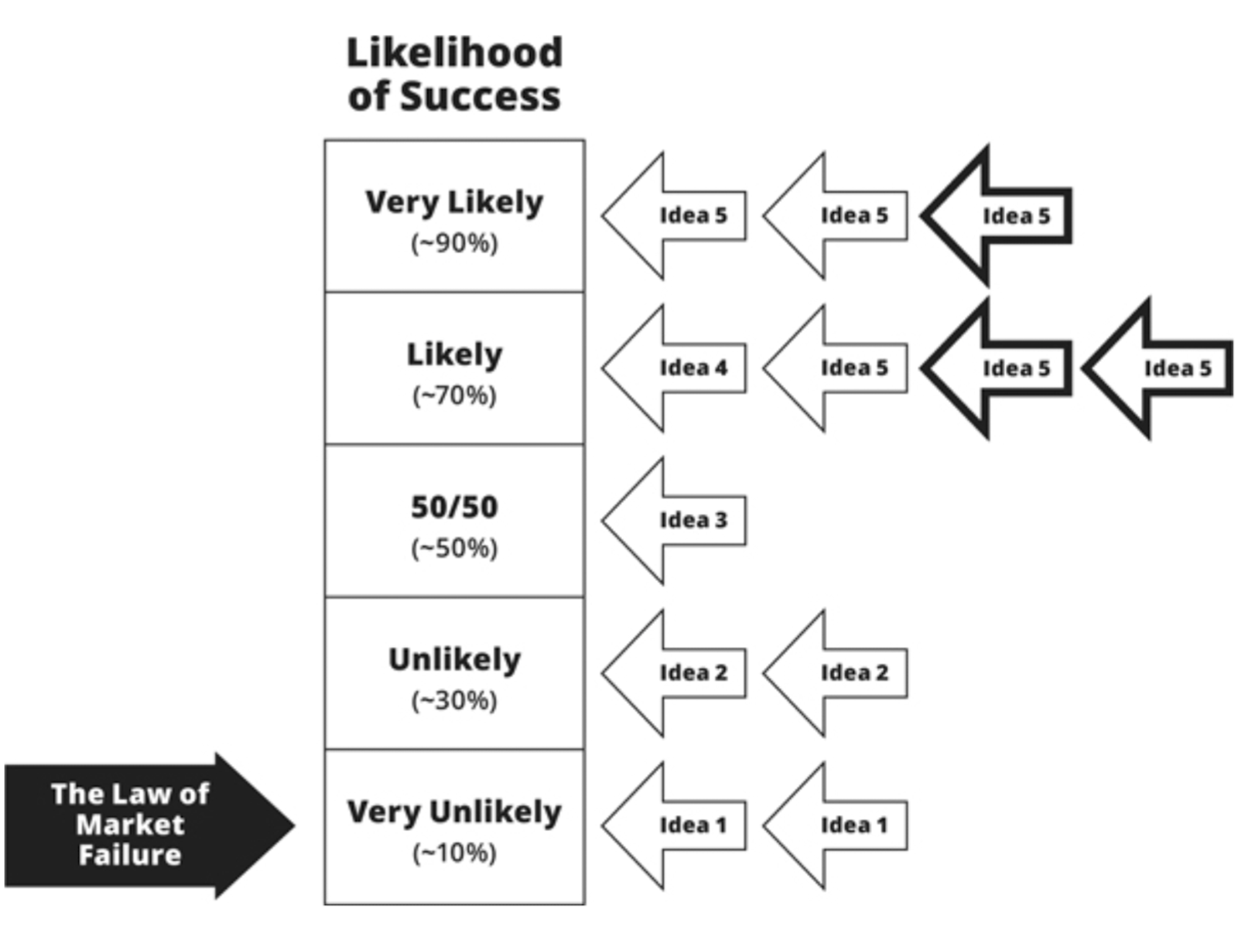

The Right It Meter (TRI Meter)

- The Right IT meter is a visual analysis tool, to help interpret the data (YODA) you’ve collected

- We begin with the presumption that our idea is guilty of being The Wrong It

- Your job is to provide enough evidence to move the meter

- Exceptional claims require sufficient evidence to support the exception

- Each arrow on the right represents a pretoyping experiment. Each experiment is designed to test a specific xyz hypothesis which is derived from your market engagement hypothesis

- For your xyz hypothesis if your data…

- significantly exceeds what the hypothesis predicts → point to very likely

- meets or slightly exceeds → point to likely

- falls a bit short → unlikely

- falls really short → very unlikely

- is ambiguous, corrupted or hard to interpret → 50/50

- A single pretotyping experiment isn’t reliable enough to determine whether the idea is likely to succeed. Many factors can skew an experiment.

- To have confidence in your results, run multiple pretotyping experiments and validate multiple xyz alternatives.

- How many do you need to run? As a bare minimum, 3-5. But it depends on…

- How much you’re planning to invest

- How much you can afford to lose

- How much certainty you need

- How conclusive the results of early experiments have been

Part 3: Plastic Tactics

Tactics Toolkit

- Plasticity is a crucial ability (to adapt one’s actions in response to new and unexpected situations)

- Think globally, test locally

- With the goal of saving time and money by early contact with the local market instead of wasting time

- You can have global plans for your product → but don’t execute against them until you’ve validated your idea on a smaller local subset of your market

- Distance to Data. Calculate your distance to data (or DTD). Get your own data (YODA) from your local neighborhood. Keep distances small to reduce friction, save time and save money. If selling online, then measure distance in digital steps. Zoom in your local digital market

- Testing Now Beats Testing Later

- Don’t delay testing, take your idea into the market as soon as possible

- Move from abstract thinking to concrete testing

- Don’t spend months or years in ThoughtLand without collecting a single piece of your own data (YODA)

- Fear stops people from having contact with the market (humiliation, disappointment)

- Don’t spend too long in ThoughtLand, don’t rush into the market → instead rush to test the market

- Hours to data. HTD (Hours to Data): measures how long it takes to execute a pretotyping experiment and collect some high quality data.

- What about capping your hours to data of 48? How would you approach that?

- Think cheap, cheaper, cheapest

- Most ideas for new products can be tested with very little money.

- Creativity loves constraints, so don’t settle for expensive experiments, challenge yourself to reduce the cost

- Dollars to Data DTD (Dollars to data):

- Tweak it and Flip it Before you Quit it

- Don’t be prematurely discouraged by disappointing YODA from your initial set of experiments

- The Right It might be just a few tweaks away

- Use what you learn from experiments to tweak your approach.

- But after a few tweaks you might to get more creative

- Techniques for creativity:

- Unpack all the assumptions you have, turn them upside down to reveal alternatives. Try the exact opposite of each one

- Do your tweaks and collect YODA from pretotypes, make contact with the market

- Pivots often happen too late, after a team has spent significant time and money

Final Words: The Right it: A recap

- Make sure you’re building The Right It before you build it right

- Most new products will fail in the market even if competently executed

- Great execution can’t save you if you’re building The Wrong It

- You need to combine great execution with a product that’s The Right It

- You can’t tell if something is The Right It in ThoughtLand. You have to take it to the market

- Other peoples data and opinions are not valuable, you need to collect your own data YODA

- Your market data must come with skin in the game. Time, money or reputation

- Thinking tools can help you articulate things in a testable form

- Market Engagement Hypothesis: XYZ. At least X% of Y will Z

- Test a smaller local market with an xyz hypothesis

- Pretotyping tools can quickly validate your market engagement hypothesis → they answer should we build it?

- Mechanical Turk, the Pinocchio, the Fake Door, the Facade, the YouTube, the One-Night Stand, the Infiltrator, the Relabel

- Measure evidence based on how much skin is in the game money > reputation > time > everything else

- Tactics and mindset:

- Think globally, test locally

- Think cheap, cheaper, cheapest

- Testing now beats testing later

- Tweak it and flip it before you quit it

- There are no guarantees

- The end to end process:

- Start with an idea

- Identify the Market Engagement Hypothesis

- Turn the MEH into a say-it-with-numbers XYZ Hypothesis

- Hypozoom into a set of smaller, easier to test xyz hypotheses

- Use pretotyping techniques to run experiments and collect YODA

- Use Skin-in-the-Game to weigh YODA.

- Decide on the next step (go for it, drop it or tweak it)

- Follow these steps and you will reduce your probability of failure. If you fail you’ll fail well. If you stick with it, you’ll find an idea that works in the end.

- Make sure you are building The Right It, and make sure that you really care about it before you build it right